Failure is Not an Option

Design: What to do. Where to do it. When it must be

done.

Methodology and goals of Design

Whenever one looks at a system, there are varying views of that

system, each view being the thing of interest to the viewer. So,

for example, a house plan looks very different to a carpenter, an

electrician, a plumber, and a heat and ventilation person. And so

it is when designing a computer system. The network people see a

whole bunch of black boxes connected by wires to switches, routers,

firewalls, etc. The computer people want to know about gigahertz,

gigabytes or RAM, terabytes of storage; but since the network adapter

is on the motherboard, it's not a concern. The facilities people

want to know about watts and BTUs/hr, and floor loadings,

lighting. The operators want to know how to fix it all when it

breaks. The bean counters want to know how much it's going to

cost. And your boss wants to know that 1) it's going to work and

2) it meets the requirements. The software engineers want to know which

software goes where and what it has to do. You must satisfy all

these competing (and legitimate) demands for understanding what it is

you want to do.

Why bother with design, why don't we just get to work and build the

damm thing? There are several reasons:

- We want to capture what the system is supposed to do

(requirements analysis)

- If the system is too big to be done by one person, then design

allows us to delegate requirements and functionality

- Design makes it easier to do a failure mode analysis

I would like to suggest that the best way to start the design

process is with a data flow diagram

(DFD). Tom

Demarco

Goals of a design

- Cost

- Performance

- Reliability

- Security

- Ease of accomodating change ( expansion and contraction) (new

software)

Cost

Performance

Reliability

Security

Strategy

Our ordinary experience with modern computers is that they are

pretty reliable. Think about it: a Pentium IV CPU with a memory

cycle time of 50 ns is doing 20 million memory operations a second and

it is common (at least, in the linux world) for them to go for hundreds

of days, roughly 1013 transactions, without a failure.

By any standard, that's pretty reliable. Most of the time, when

the computer does fail, it is a dammed nuisance but no big deal (you do do backups, don't you?) So

what is the problem?

Reality rears its ugly head

The discussion to the right made the explicit assumption that the two

computers will fail independently.

In fact,

the computers may fail dependently, and my experience is that dependent

failures are far more common.

Why do computers fail dependently? Because they have things in common

that can fail:

- There could be a power problem with a single rack (lesson: don't

put the redundant computers on

the same rack).

- There could be a power problem with one or two

phases of power - this is relatively unusual but it does happen

(lesson: don't put the redundant computers on the same phase - have

your electrician label each outlet by phase) (Another lesson: three

phase motors (common in HVAC equipment) should be rigged so that a

failure in amy phase will pop the breakers which is safe instead of

letting the motor cook which is dangerous!)

There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader).

There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader). - There could be a router failure (lesson: don't put the redundant

computers on the same network).

- Floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, hurricanes, riots, bombs (and

bomb threats), heat waves and cold spells. For

example, I've seen a water pipe

burst above a rack. Which was filled with a million dollars worth of

equipment. Which the US Air Force loaned to us. Fortunately, I was able

to roll the rack out of the way, but I was drenched in the process - we

were lucky somebody was in the room at the time.

- The database could go down, for any of a number of reasons

(uh-oh). For example, I've seen

queries which have scrambled the indices of a database, which caused

the database to slow to a crawl,

which in turn caused intermittent failures in the application.

- There could be a problem with the software (double uh-oh). That

only manifests itself in production (triple uh-oh).

- Production computers are at risk for cyber vandalism - the

internal test computers are not

since they aren't exposed to the internet.

- "human" problems: stupid sysadmins, malicious sysadmins,

surreptitious bad guys (who get into the

server room by stealth or guile), mighty bad guys (who get into the

server room by force). Who knows what clowns

facilities is letting into

the cable closets?

- Mechanical systems (fans, disk drives, connectors) wear out. (see

"Safe Life", below)

Failure resistant

It is possible to build systems that are failure resistant. In

other words, they don't fail. Pfail

is small. There are several strategies for

achieving failure resistance:

- The system can be over-engineered to withstand several factors of

worst cases stresses. Classic examples are bridges and

dams. A simple example: use fans with ball bearings. They

cost more but they last forever. Over building power supplies (a

500 W power supply when 250 W is plenty). Derating components

(running them slower than spec'd) is another way to make a system more

reliable. Keep the systems cool.

- The system can have internal redundancy so that externally, the

system appears to be reliable. Hardware RAID-5 is a classic

example: your computer perceives a system that never breaks.

We had a network attached storage

machine, a black box, with a couple of hundred gigabytes of storage in

it (this was in the days when hundreds of gigabytes was a big

deal). One day, we got an E-mal from the box that said that it

was broken, and we should expect a part to arrive shortly. A few

minutes later, we got an E-mail from the vendor that said that the part

had been shipped. So we went down to the server room and found a

yellow LED that was on on the front of the black box. That

afternoon, we got another E-mail saying

that part had arrived at the local airport and had been loaded on a

truck. We got another E-mail with instructions on how to replace

the part. The part arrived. We followed the

instructions and swapped parts. The yellow LED on the front of

the box turned

off. We never found out what went wrong, but the users never ever

had a clue that anything was amiss.

- The system may have a "safe life". For example, you may

decide that a system will be in service for three years and then

retired, either scrapped or turned into a development machine.

Most failures occur either at the beginning of a machine's life, when

the manufacturing defects manifest themselves, or near the end of life,

as bearings wear out, capacitors get leaky, and chips self destruct

from their own waste heat. A failure in a development environment

is a dammed nuisance, but a failure in production is a disaster.

- Use Error Correcting Code (ECC)

RAM whenever possible. Use parity RAM if not. If a machine

has neither parity or ECC, probably it is best not to use it.

- Test in failure mode. Try running your systems with one or

more components either turned off or disconnected. If you are

really brave, or confident, you can try pulling the power cord in the

middle of an operation and see what happens. If you are not quite

so brave, you can always do a kill -9 on some critical

daemon. If the system fails in test, then you can go back to the

drawing board and engineer it again. Once you are in production,

you don't have the option.

- Training your operations staff. That includes not only how

to do things, but why. An amazing number of system failures

happen due to stupid mistakes. Develop

this more

- Thinking in terms of reliability, and learning lessons.

One day, I was working behind a

rack of computers with a monitor and a keyboard on a cart. I had

accomplished my task, so I pulled the keyboard cable, the VGA cable and

the power cable. Unfortunately, I made a mistake tracing the

power cable (they're all black) and pulled the power cord to a

server. Of course, the moment I realized my mistake, I plugged it

back in, the server started, ran fsck no problems (ext3 file system,

thank god) and booted. But the monitoring system caught me and

the boss sent an E-mail to one and all asking why the server

rebooted. Busted!

Now, all of the power cables for monitors have unique colored PVC

ties at the end so that it is easy to identify them in a rats nest of

thick black cables.

The problem is that computers don't fail in the same way that dams and

bridges do, so it is hard to imagine ways of applying what works so

well for civil engineers. Furthermore, WHAT?

Fail safe

All around the world, railroads

meet roads at grade. It's the cheapest way to get the tracks to

the other side of the road. At low traffic railroad crossings, a

couple of wooden or metal signs are sufficient. At high traffic

crossings, there are signs, paint on the roadway, lights at eye level,

lights on a tower cantelevered over the road, barriers to prevent cars

from crossing the tracks. Some of these crossings are at very

remote locations. How do they work reliably? There is a

circuit in the track. At the far end of the circuit is a power

supply. At the near end of the circuit is a voltage sensor.

If

anything goes wrong with the circuit, such as a broken power supply, a

broken wire, a broken rail, or a train, then the signals activate and

stop traffic. The system is fail safe.

Fail safe systems are wonderful things, but you can't always

implement them. Aircraft "fly by wire" systems simply cannot

fail, because if they do, then the airplane will crash within seconds.

Failure tolerant

The wave of the future seems to be in inexpensive failure tolerant

systems. You know that your subsystems are going to fail, so you

engineer your systems so that the failure of a subsystem will not cause

a failure of the system. If you have N redundant systems, each of

which has a Pfail

which is small, Psystem_fail

= Pfail N which is very small (if you

need

M systems to run, then Psystem_fail

= Pfail

N/M). These

technologies have

names: RAID (Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks), (VIPs) Virtual IP

addresses, VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks.

Achieving failure tolerance through redundancy

When having a discussion about computer systems, it helps to pick

the appropriate level of abstraction for the discussion at hand.

This discussion of failure tolerance will go through decreasing

abstraction.

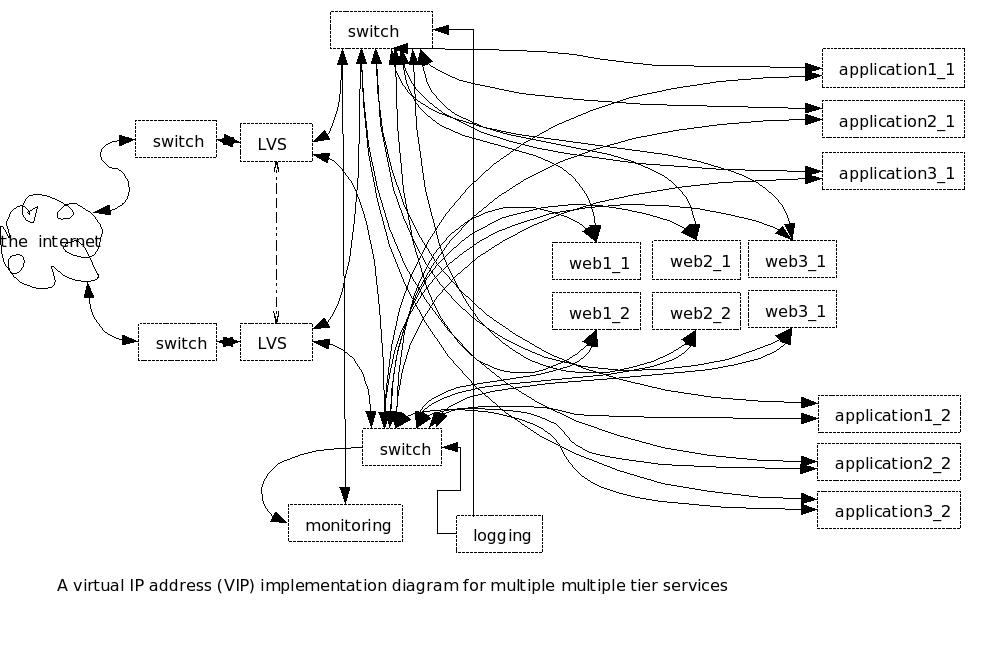

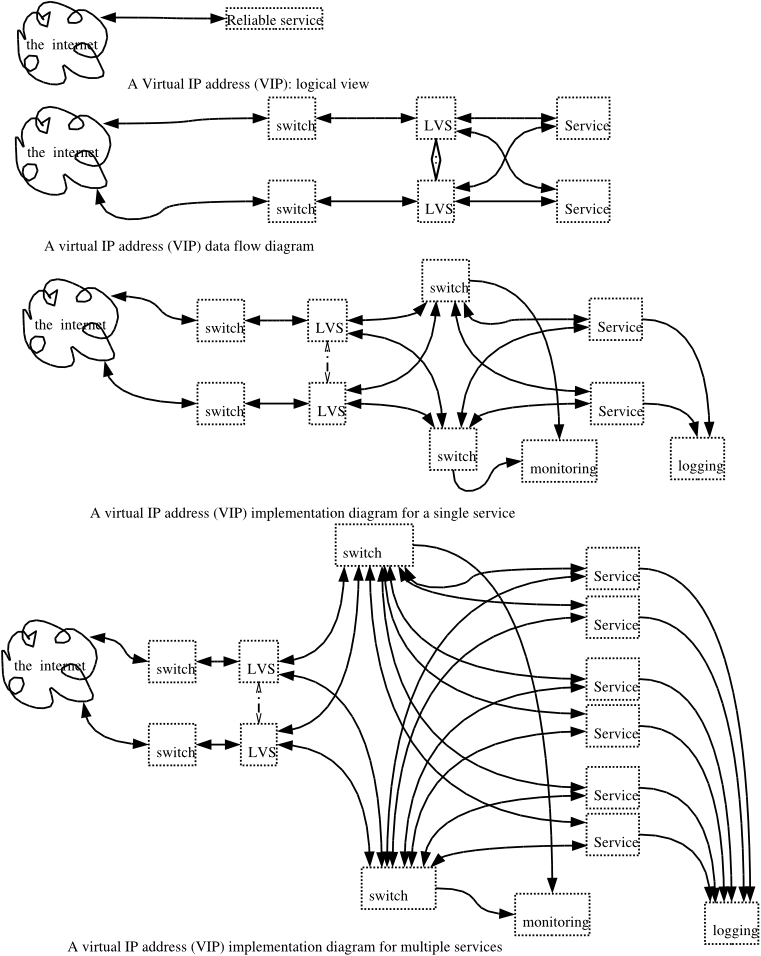

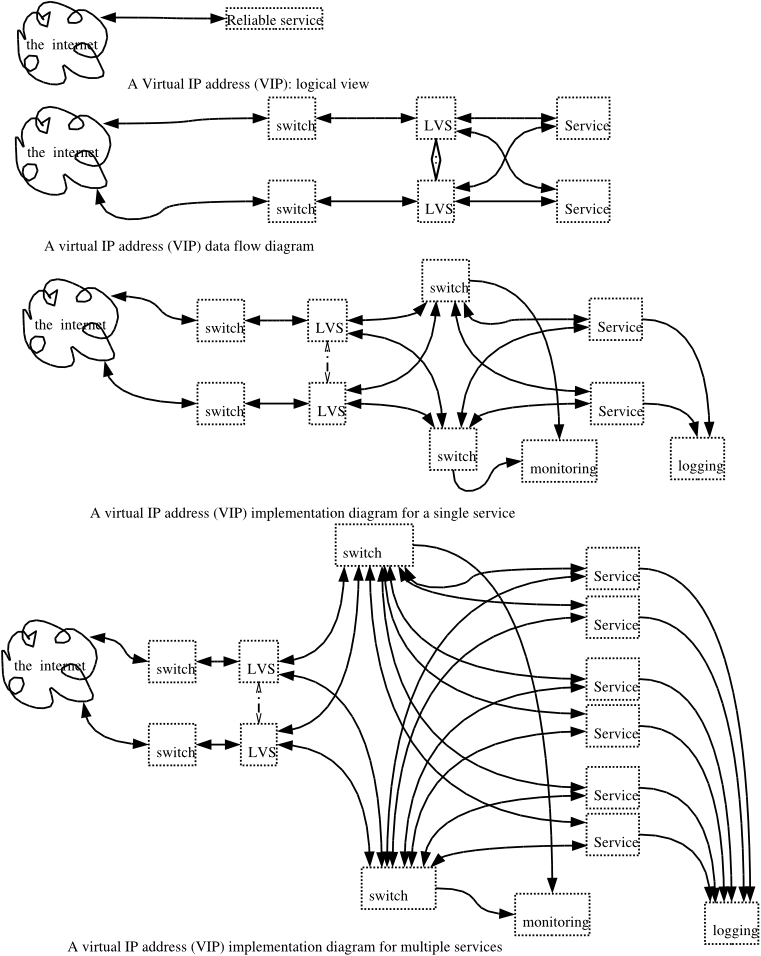

Figure 1 shows the evolution of a failure tolerant system. The first illustration

shows how a failure tolerant system appears to the customers.

Notice that they don't see any of the complicated stuff: they perceive

a highly reliable system. This is as it should be.

The first illustration

shows how a failure tolerant system appears to the customers.

Notice that they don't see any of the complicated stuff: they perceive

a highly reliable system. This is as it should be.

The second illustration shows a logical view of a failure tolerant

system that provides a single service. This is the view that the

programmers see. Why do the programmers see the switches, which

are normally transparent? Because the switches implement Network Address

Translation (NAT). The

switches also have Access

Control Lists (ACLs), which function as firewalls and limit the

kinds of traffice that can get to (and from) the internet. Note

the Linux Virtual Servers (LVSs).

The third illustration shows a implementation

view of several services implemented in the same system. It is

possible to amortize the cost of the infrastructure (the switches, the

LVSes) over several services. Switches and LVSes are remarkably

fast compared to web servers and application servers, and there's no

reason not to use them for more than one service.

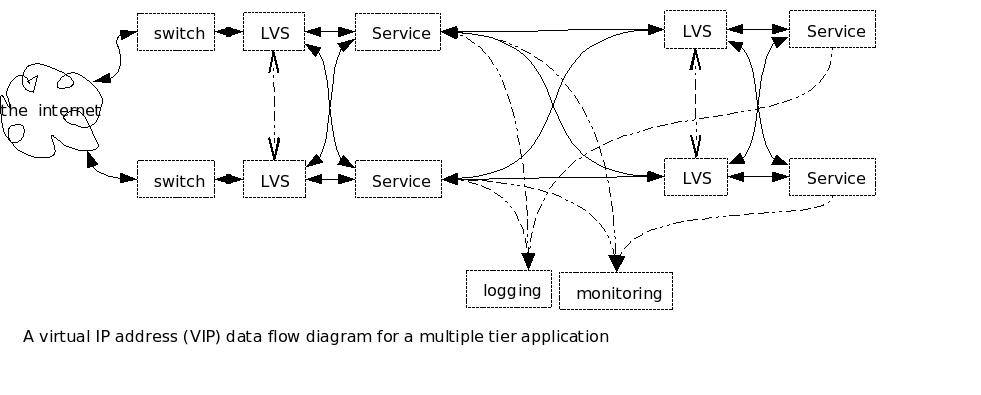

All of these diagrams are single tier (or two-tier if you count the

customer's system as a tier, which some writers do). If you are

implementing a multi-tier system, then you have to have redundancy not

only for the front end but for the back end as well. However, you

can use the same LVS hardware to front the front end service but also

the back end server, thereby presenting the appearance of a reliable

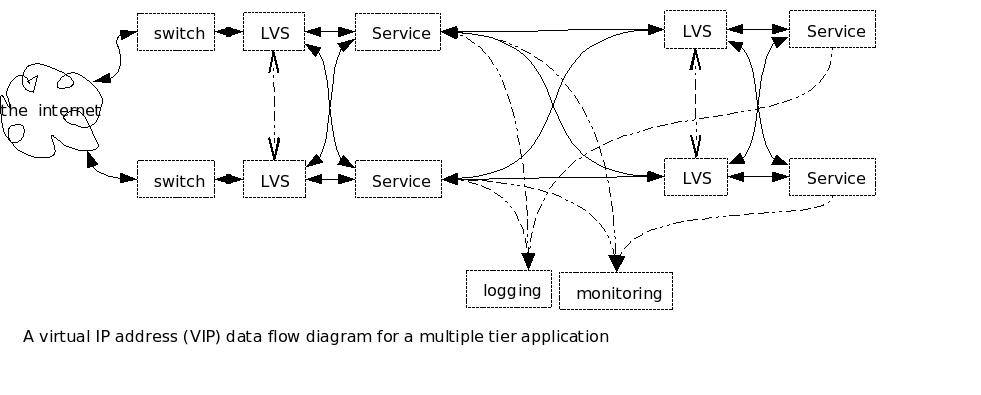

back end to the front end. Figure 2 shows a Data Flow Diagram of

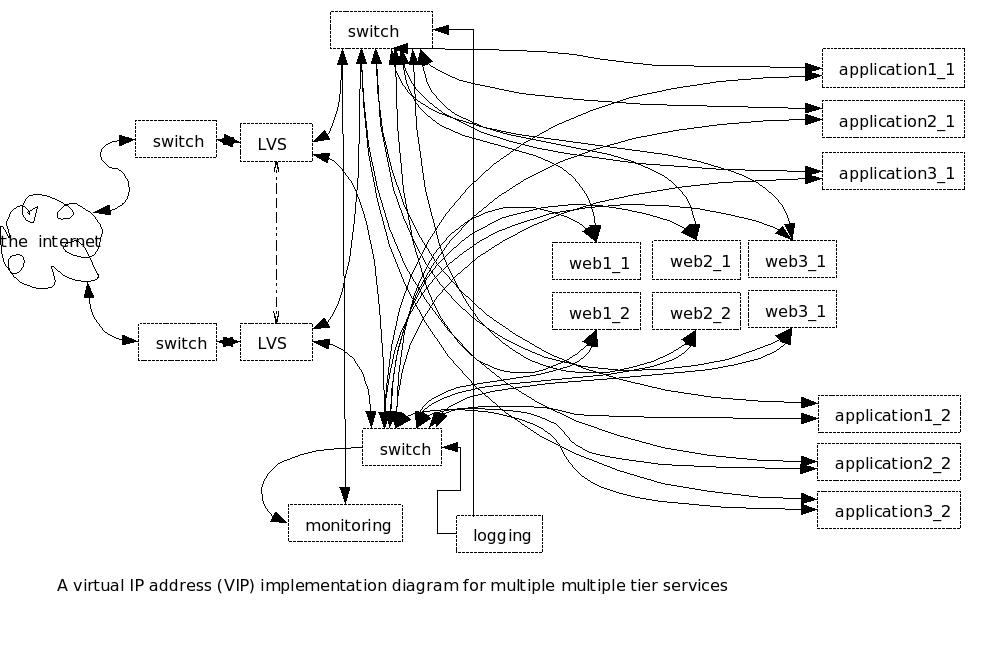

a multi-tier system.  Figure 3 shows how this might look (in case you ever wondered why

modern PCs have two ethernet ports).

Figure 3 shows how this might look (in case you ever wondered why

modern PCs have two ethernet ports).

This seems rather daunting, does it not? Well, there are some

tricks you can use. Assuming that your applications are

lightweight enough, you can combine multiple applications onto a single

computer. You do this by getting clever with IP addresses, Ports, Operating Systems, processes, images, and threads. There are (at least)

three ways to do it:

- Single Operating System, Single IP address, multiple ports,

multiple processes, single or multiple images, single threads.

- In this approach, there are several UNIX processes, each with its

own memory space. Each image listens on its own port but shares

an IP address with the other processes on a system. If any single

process fails, the other processes keep going. Each process can

get a full memory space, 4.3 GBytes on an 80386 class-computer.

The problem with having a single image over multiple ports is

allocating work to the different processes. If different front

ends connect to different backends, that can solve the problem

nicely. Having the front end on different ports for different

processes with the same image is problematical for the users. But

if each image, each application type, is on its own port, than this

scheme can work quite nicely. Incidentally, "single threads"

means that each process has a single thread of execution. But

there can be a main application whose sole function is to listen for an

inbound connection and then fork a

child process when the connection arrives. The main application

loops and listens, while the child process does whatever needs to be

done and then exits. If the child process has an error, then that

particular transaction dies but the main application process keeps

going.

- Single Operating System, Single IP address, multiple ports,

multiple processes, single or multiple images, multiple threads

- Modern UNIXes have the ability to spawn multiple threads of

execution within a single process. The threads share a single

address space. Keeping the memory seperated between the threads

is a challenging proposition. Advocates of threads, as opposed to

processes, argue that threads require less attention from the OS than

processes, and they're correct. But in this modern age with very

very fast computers, I don't that a compelling argument.

- Single Operating System, Multiple IP addresses

- Linux (check other operating

systems) has the ability to bind several IP addresses to a

single physical network connection through a mechanism called "IP

Aliases". Each application listens on an IP address

appropriate for the service it is providing. So, for example, one

IP address can serve as a front end, and another as a backend, and

still another for monitoring and yet another for logging.

Switches and hubs will work with this approach, since they work at the Ethernet (MAC)

level. The machines that talk with these machines do not realize

that while the IP addresses are the same, the ethernet addresses are

different. But the switches that connect them together see

Ethernet (or IEEE 802.3, not much difference here) packets and happily

send those packets where they're supposed to go.

- Multiple Operating Systems.

- You can virtuallize the operating system (OS). Each

application, or group of applications can run in its own OS, which need

not be the same OS as the "real" OS. It is possible to have

multiple virtual operating systems on the same machine. VMware ®

is a classic example. Virtual Operating Systems can communicate

with one another using TCP/IP, so it is possible to have a virtual

network inside the physical machine.

Using some combination of these tricks, one can build a highly reliable

system using two switches, 2 LVSes, 2 severs, and 2 database servers

(if appropriate).

There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader).

There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader).  There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader).

There could be a power failure of the whole room,

or even the whole floor, or even the whole building,

or even the whole city (lesson is left as an exercise to the reader).  The first illustration

shows how a failure tolerant system appears to the customers.

Notice that they don't see any of the complicated stuff: they perceive

a highly reliable system. This is as it should be.

The first illustration

shows how a failure tolerant system appears to the customers.

Notice that they don't see any of the complicated stuff: they perceive

a highly reliable system. This is as it should be. Figure 3 shows how this might look (in case you ever wondered why

modern PCs have two ethernet ports).

Figure 3 shows how this might look (in case you ever wondered why

modern PCs have two ethernet ports).